Internet book review by W. Dörge-Heller, ”Shakespeare

and the Dark Lady” (www.lebensraeume-var.de/darklady - update 5

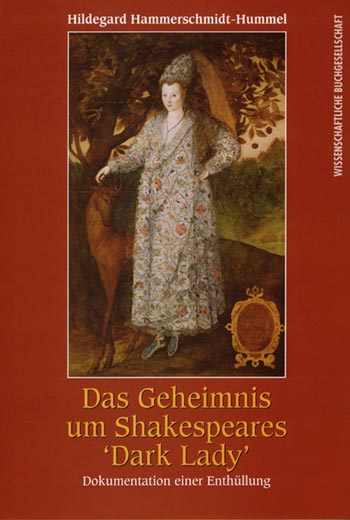

April 2003) (On Das Geheimnis um Shakespeares ‘Dark Lady’/

The secret around Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’) -

Excerpt:

”The article deals with the theses of Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel on the identity of the ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The work ‘The secret around Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’: Documentation of disclosing a mystery’ was published by Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, in 1999.

The Identity of the Dark Lady’

According to the theses of Mrs Hammerschmidt-Hummel

First of all H[ammerschmidt-Hummel] presents thoroughly and understandably that Renaissance paintings are to be interpreted differently from present-day works of fine arts. They contain codes, allusions, emblematic riddles and their solutions; the want to be ‘read’. It is a perfect fit that the painting in question has, so to speak, a headline that consists of three parts as well as a complete sonnet at the edge. This means that the painter himself suggests a transition from viewing to reading. It is well-known that many Renaissance works of art have such an encoded approach to their contents – as, for example, the works of Giorgione. Thanks to the astute analyses of Hartlaub, Saxl and Panofsky we have insight into the highly spiritual background of that age. Now to the interpretation of the painting of H[ammerschmidt-Hummel]:

1. The portrayed ‘Persian Lady’ is Elizabeth Vernon, a high-ranking lady at the court of Elizabeth […]. She is pregnant but – in spite of this probably happy expectation – is surrounded by symbols of melancholy and mourning.

2. Elizabeth Vernon is the hitherto unknown ‘Dark Lady’, who in Shakespeare’s sonnets is addressed in various ways (beseeching, tender, but also angry and condemning).

3. […] the third person, the poet’s friend, who is mentioned in the sonnets, must be the lover and later husband of the ‘Dark Lady’: […] Henry Wriothesley, […] Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s […] friend and patron.

4. […] the consequences of this relationship, a child, came to light in two extant [Elizabethan] paintings. For reasons of solidarity with the poet the painter seems to have followed his [Shakespeare’s] instructions.

5. The consequences of this difficult constellation for

all persons involved: Let us first speak of the two opponents. The loss

both of them suffered is grave; their friendship is obviously broken for

good. Shakespeare himself had never wholly got over the separation from

the ‘Dark Lady’. It cannot be excluded that he had hoped for

further children from a lasting relationship since his son Hamnet had

died during his lifetime and since his wife could not [as it seems] have

any more children. That Shakespeare had apparently never been able to

cope with the situation entirely can also be deducted from the fact that

at a certain time in his life he had his sonnets published. This unfolding

of the personal, even intimate situations in the sonnets must have been

a serious blow for the two other persons involved. Thus Shakespeare possibly

hit his rival directly and lastingly. It is not in the least astonishing

that the Earl of […] Southampton despite all his later political

successes always seemed to have been malcontent. It is, however, possible

that this was part of his character. […]

Recognition and criticism

On the theses and the proof of evidence

H[ammerschmidt-Hummel]’s approach to the problem is as astute as it is unorthodox. Remarkable the detailed analyses of the painting, especially there where the Countess in her bedchamber unintentionally reveals her illegitimate relationship to the viewers of the painting. Her interpretation of the inscription and of the sonnet, the best part of the book, should be correct in all its details. With great sensitivity Mrs H[ammerschmidt-Hummel] then analyses the various consequences of the situtation enlightened under the new circumstances with regard to the poet’s artistic work and the particulars of his later life. The way in which she integrates the new sonnet into the development or termination of the ménage à trois and thus is able to newly interprete the whole sequence of events demonstrates, in addition, a remarkable ‚poetical intelligence.’

Insofar, it seems to me, Mrs H[ammerschmidt-Hummel]’s argumentation is conclusive in all important points. In view of the significance of this contribution to the history of literature and art we can speak of a great success (”einem großen Wurf”), for which we owe Mrs H[ammerschmidt-Hummel] great thanks. ...”

***